- Home

- Brian S. Wheeler

Jimmy Jack and the Smartman Page 2

Jimmy Jack and the Smartman Read online

Page 2

Chapter 2 - Tomatoes and Folly

I'm shivering in the last antechamber where a person has to wait before entering the bubble chamber to visit the smartman. As always, my breath turns to vapor because of the chill, but Jason John, who works as a member of the smartman's security, takes his time frisking me to make sure I'm not carrying anything into the bubble chamber that might endanger the smartman. I remember how Jason John was such a snot growing up in my neighborhood, and I'm not proud to admit that I still struggle to understand the smartman's thinking in hiring Jason John. But, I remind myself, the smartman thinks in complex ways.

"You sure you're not carrying any germs into the bubble chamber?" Jason John's eyebrow arches.

"I know the routine, Jason John. I'm not wearing anything but a shirt and shorts into the bubble chamber to cut down the risk of germs. This isn't my first dance."

"Then why you wearing those long sleeves?"

"Because it's always freezing in here."

Jason John snarls. "Those long sleeves look as ridiculous as your cut-up, denim shorts. And it's scorching outside. You want to just leave whatever you're trying to sneak into the bubble chamber here with me, or do you want me to kick your ass out of the complex after I discover whatever it is you're keeping up your sleeve?"

"Alright, Jason John. You've caught me. The newspaper here is all I got."

Jason John chuckles as I toss the paper into the plastic cube, currently holding the keys to my hovermudder and my wallet, that sits outside of the smartman's bubble chamber. I never bring any money with me when I visit the smartman, as I've learned Jason John doesn't hesitate to help himself to anything the smartman's visitors must leave behind in the antechamber. My socks and shoes fall into the cube before I slip my feet into the latex slippers Jason John tosses to me a moment before he helps slide my arms into a plastic jumpsuit. A hairnet completes my attire, and so I become "bubbled-up" as those who visit the smartman as routinely as myself are fond of saying. The air hisses. My ears pop. Jason John nods as the door on the far side of the antechamber slides open. My latex slippers squeak and my plastic outfit crinkles as I step into the bubble chamber that houses our community's smart man.

I think my neighbors take the smartman for granted. I don't. I pay attention to the stories our community's news outlets try to gloss over. I suppose I've always had a knack for reading between the lines, a habit that caused my poor parents all kinds of grief before, Maker bless their souls, they passed before learning to understand why their son couldn't simply accept the way things were. I always try to see both sides of a coin. So I suspect I've noticed a few things my neighbors haven't - that the smartman isn't getting any healthier or younger, that many a community's smartmen are dying, that our own smartman isn't going to be around forever to listen to our concerns and give us advice. I like to think I appreciate the smartman better than most, and I like to think that sentiment is going to bring me some good luck to go with whatever advice my town's smartman decides to hand me today.

And unlike any of my neighbors, I tend to pity the smartmen far more than I envy or resent them. I don't experience the satisfaction my neighbors feel when they repeat the history of how all those smartmen found themselves placed in their plastic bubbles, each week required to hear the concerns of their community and to freely give their honest advice. I don't share my neighbors' opinion that the Maker was just to so cruelly punish all the smartmen.

Many decades ago, the ancestors of our modern day smartmen represented the wealthiest members of our communities. According to histories my neighbors tell, those smartmen ancestors spent all their gold to learn how they might modify all the tiny genes that define a person. The wealthy back then realized that those itty-bitty genes gave a person far more than blue eyes and blonde hair. They realized those genes could give their children all the traits they resented hadn't been given to them. They knew that genes held the power to place their girls and boys upon pedestals far above those who did not hold piles of gold. Thus many decades ago, the wealthy spent their golden piles so that their children would be more beautiful, so that their children would runner a little faster for a little longer, so that their children would be wiser and more clever, so that their children would push the poor and the meek a little deeper and deeper into the mud.

Those wealthy ancestors became purer, and richer, with each generation. The rest of us just got dirtier and poorer. Tweaking all those genes grew more and more expensive. Fewer and fewer could afford to modify their offspring's genes at all. History evolved. A time arrived when there were those who were simply born better than the rest, and those few held all of the keys. I doubt many questioned such a hierarchy. Everyone likely considered it all was just the way the good Maker wanted it.

That was until the powerful and the affluent turned ill.

The stories shared from one neighbor to the next suggest that those folks who tweaked their genes so far must have made a fatal error by leaving something out of the mix. The first cases of the plague exploded a little more than forty years ago. None of the poor ever felt any of that plague's symptoms. None of the ghettos and slums reported an instance of any of their residents falling ill. But the plague spread like fire through those wealthy few who had tweaked their genetic code so far. Purple and orange splotches expanded just beneath the skin. Victims bled from their noses and eyes. They shook with fever. They would spasm and vomit for a week or two after the appearance of the first blotch, but none who had pushed their genes so far, and thus contracted that fever, survived for very long after their faces began bleeding.

That plague really shook things up.

The meek, who had never been able to afford improving any of their genes, switched places with the wealthy and the powerful. Most communities and nations didn't lift a finger to help those whose modified bodies possessed no defense to the plague. Most places were very happy to watch those whose faces bled suffer and perish. Most places wasted no time before looting the emptying mansions. Most of the poor lost no sleep after stealing the toys once cherished by the rich. And it wasn't very long at all until those places were burning with the fires of riot as anarchy filled the void left behind as those affluent leaders died to the fever.

But other places, like my community, judged it would be a shame to lose all those minds which had been made so wise through so many generations of genetic modification. A few places, like my community, were not so confident they might survive, and prosper, if the plague was allowed to so quickly erase those who had guided us for so long. Oh, things would change. There wasn't a community across the country that would any longer be so subservient to the those with the modified genes, but that didn't mean everyone was ready to just watch all of those with tweaked chromosomes bleed and shiver in the grips of that plague's fever.

Not even the modified wise could isolate the source of the plague. Some argued the plague was but the erosion of cells whose genes had been pushed too far, that the problem was an internal one without the influence of external pathogens. Others believed the opposite. Thus communities like mine built the bubble chambers to house a smartman, or smartwoman, who yet remained untouched by the plague. We followed the smartmen's advice and shielded them within spheres of plastic. Following their instructions, we installed all the filters and precautions needed to prevent any possible pathogen from touching the smartmen's skin.

We didn't do it free of charge. We made those smartmen promise to listen to the needs of the poor and the dumb. We made them promise to listen to our problems and give us their advice. None of us are afraid to remind any smartman how easy it would be to pop the plastic bubble that protects him should he fail to live up to his end of our bargain.

"Ah, Jimmy Jack, I'm so happy to see you back again this week. I so enjoyed our previous discussion."

"I'm very happy to be back, Yogi."

I'm proud to be on a first name basis with my community's smartman. It makes me feel like all those hours spent waiting in line to speak

with him are worthwhile.

The bubble chamber rests in the very center of the large, domed municipal building constructed in the center of our community. Offices surround the building's exterior, but the bubble chamber's dome rises high above the level of those offices to stand above any of our community's other buildings. I've always liked the sight of that golden dome standing in the foreground of the green mountains that hem our town on three sides. I've heard that the design of the plastic bubbles differs from one community to the next. I hope our town has done well in constructing our plastic bubble.

I've heard some communities make their smartmen stand whenever listening to their community's travails. I wouldn't like to do that to our Yogi. My community has provided Yogi with many comforts - fine and comfortable furniture, bookshelves brimming with leather tomes, computers and televisions for entertainment, fine china and silver for dining. We like to think a comfortable smartman helps insure we receive the very best of advice.

I worry that Yogi would suffer without his comforts. He's so thin that it takes no effort to discern the bones beneath his skin, skin turned almost white due to the artificial lighting of the smartman's confines. Yogi's arms and legs look several inches too long, and the rest of his core is thin as a spindle. Yogi's head is an oversized melon, and I'm often amazed that Yogi's neck finds the strength to raise his chin. Yogi is wearing the beige and maroon smoking jacket he wears each week while conducting his court. He must regard it, and the dark slacks draping his legs, as a kind of uniform. Yogi's eyes are swollen, with dark bags of skin surrounding them. His hair grows thinner and more sparse with each week. He looks tired. He doesn't look well. I hope Yogi hasn't fallen ill.

"I've been thinking all week about that strain of quinoa plant." I have to pay attention and focus to hear Yogi over the air filters that constantly hum on the surface of the smartman's bubble, "I believe I've found a way to overcome the pollination challenges the quinoa faces when planted in this climate."

I shift my weight from one foot to the other, trying to remember what Yogi is talking about in order to be polite.

Yogi perceives my posture and sighs. "You were asking me last week about your garden, Jimmy Jack. I thought you wanted to learn how to get the highest protein yield possible from your effort."

"Oh," I smile. Sometimes, it's hard to follow how Yogi connects so many things together in that big head of his. "I only wanted to know when it would be best for me to plant my tomatoes."

"But don't you want to make the most of your garden?"

"I only want a good tomato and mayonnaise sandwich."

Yogi frowns. "And what did I tell you last week?"

"You told me you were worried that the climate was turning too dry for tomatoes. You told me you were worried about the ground going bad. You told me it would likely be very hard for tomatoes for a very long time to come."

Yogi rolls his eyes. "Let me guess. You planted those tomatoes all the same."

One has to be patient sometimes when speaking with a smartman. Sometimes, you have to give a smartman like Yogi a little time before the good advice starts flowing.

"I always plant tomatoes, Yogi."

"But you're wasting precious space and resources with the effort." Yogi shakes his head in disgust. "Jimmy Jack, I worry myself sick thinking about the coming day when this community isn't going to be able to feed itself. The climate is only growing worse. Quinoa can be a salvation. I know quinoa is not the same as tomatoes, but that crop can thrive even here with a little help. It's a healthy protein, and you could grow more of that plant in your garden than you ever could tomatoes."

"I like tomatoes."

"Because it's all you know, Jimmy Jack. For once, I wish someone in town would listen to my advice. I wish someone would try something new."

"I haven't heard of any of the other communities planting quinoa."

Yogi fails to keep his voice from rising, poor form for a smartman. "All the more reason to plant quinoa here, now. You could start a new revenue stream."

After you've visited a smartman as many times as I have, you get a sense when you need to keep your opinions to yourself and just nod so that you can sooner get to whatever topic you bring to the bubble.

"Alright, Yogi. I doubt I'm going to find any quinoa recipes in my grandma's book of cooking, but I trust you. If you feel so strongly about that plant, I'll be sure to plant it in my garden."

Yogi grins. "And you promise to help pollinate the plants just as I say?"

I nod, though I don't plant to waste any time playing around in the dirt. I never spent too much time playing around with my tomatoes.

"I'm glad you've come around to my way of thinking, Jimmy Jack. Tell me, what brings you to see me this week?"

"I'll need to have a piece of scrap paper and a pen again for this one, Yogi."

That brings a spark to Yogi's eyes. "You must have a fine issue to discuss this week if you need to take notes. Help yourself to one of those notebooks on the counter behind you."

"Ah, thanks, Yogi. Can I keep it?"

"Of course. Once you take anything out of the bubble chamber, you cannot bring it back in."

"Are you ready to hear what I have to ask?"

"I'm ready."

I take a breath and rush through my question. "I want to know what six numbers I should use for this week's lottery. Plus the seventh number for the power ball."

Yogi's face turns a whole new shade of white. His oversized, melon head falls onto the back cushion of his leather chair. He appears to close his eyes and count silently.

"Of course, Jimmy Jack," Yogi sighs. "Everyone's asking for numbers to play in the lottery."

"The jackpot's real high, Yogi. No one's won it in a good while."

"Sure, Jimmy Jack," Yogi's eyes remained closed, "but I'd hoped you would have something more important to ask me about. Something more worthwhile of my time."

"It's plenty worthwhile to me, Yogi. There are more zeros connected on the end of that jackpot's number than I can count. It would be very worthwhile to me indeed if your advice would help me win it."

"Jimmy Jack, you do realize that those numbers are generated on pure, random chance. Don't you, Jimmy Jack? There's no science behind it. There's no method to help me judge if one number might be better than a next number. You're winning odds do not improve the least if I provide you with seven numbers."

I'm a veteran when it comes to visiting the smartman, but Yogi still confuses me from time to time. One moment, the smartman talks like he knows everything under the sun. The next moment, the smartman doesn't give himself any credit at all.

"I sure would appreciate some numbers all the same, Yogi. Look at it this way. I think you're a bit of a good luck charm. Consider my asking a kind of compliment."

"Seven. Eleven. Twenty-two. Thirty. Thirty-one. Thirty-seven. Forty-three for the powerball."

My hands hurry to scribble those numbers across the first page of that notebook. I have to ask Yogi to repeat that string of digits. He grumbles, but he repeats the numbers without a stutter. I stare a moment at those seven digits I've jotted in the notebook. They look like good, solid numbers to me, and Yogi promises he hasn't given that same string of numbers to anyone else who's asked, that he won't give duplicate strands of numbers to anyone who visits him that day no matter how many times he's asked to supply them. Before I leave, I promise again to Yogi that I'll plant whatever seeds he supplies to me in my garden.

The winning lottery numbers are broadcast at the end of the week on television, and my eyeballs are glued to the screen while I watch the ping-pong balls float into the soft hands of that blonde bombshell who smiles while showing each number. I don't have a single digit by the time the final, seventh ping-pall ball rises out of the hopper. I don't understand how Yogi can be so smart until it comes to something practical like lottery numbers. I wonder if those ping-pong balls might be fixed. I like that thought, because I so look forward to my weekly visits with the smartman, an

d this life would be mighty tough if I couldn't trust him for advice.

* * * * *

Polish, Dust and Sparkle

Polish, Dust and Sparkle Old Hunters on the New Wild

Old Hunters on the New Wild Mr. Moon's Daredevil Messiahs

Mr. Moon's Daredevil Messiahs Opus Wall

Opus Wall So That a Marigold Might Live Free

So That a Marigold Might Live Free Firedrop Garnish

Firedrop Garnish Jimmy Jack and the Smartman

Jimmy Jack and the Smartman Given to Glass

Given to Glass The Sirens' Last Lament

The Sirens' Last Lament Keepers of the Automata

Keepers of the Automata The Warden's Mark

The Warden's Mark The Provenance of Monsters

The Provenance of Monsters Cat-Tooth Magic and Dog-Eared Miracles

Cat-Tooth Magic and Dog-Eared Miracles Heritage and Shimmer

Heritage and Shimmer Words Burned to Flame

Words Burned to Flame Harpies of Planet Sutherland

Harpies of Planet Sutherland The House on Maple Street

The House on Maple Street Not All Spirits Be Foul

Not All Spirits Be Foul Men Wore Hats

Men Wore Hats Shadow Weapons of Doom

Shadow Weapons of Doom Glorious Gardens of Teetering Rust

Glorious Gardens of Teetering Rust Butcher, Baker and Replicant Maker

Butcher, Baker and Replicant Maker Patriots of Griffin XIII

Patriots of Griffin XIII Bones in Daylight

Bones in Daylight Trophy Grove

Trophy Grove Grandchildren Returning Their Spoils

Grandchildren Returning Their Spoils Floating the Balloon Bombs

Floating the Balloon Bombs Starlight, Starbright

Starlight, Starbright The Resonance of Sweet Mrs. Queen

The Resonance of Sweet Mrs. Queen Brother Keepers

Brother Keepers Legacy of the Chain

Legacy of the Chain The Dusty Dead in the Valley of the Blossoms

The Dusty Dead in the Valley of the Blossoms Thus the Starfly Vanish

Thus the Starfly Vanish A Cruel and Burning Ice

A Cruel and Burning Ice A Voice That Summons Monsters

A Voice That Summons Monsters The Beckford Bottom Beast

The Beckford Bottom Beast The Llungruel and the Lom

The Llungruel and the Lom The Meek

The Meek Depth of Field

Depth of Field Mary, in Need of Belle

Mary, in Need of Belle Memory, Light & Medicine

Memory, Light & Medicine The Tent in the Gymnasium

The Tent in the Gymnasium Rooms Without Furniture

Rooms Without Furniture A Handicap of Shades

A Handicap of Shades Glass Desires

Glass Desires Risen for a Tower

Risen for a Tower Kennel, Kingdom and Crown

Kennel, Kingdom and Crown Plastic Tulips

Plastic Tulips Guarded Keepsakes

Guarded Keepsakes Zombies Earning Their Hunger

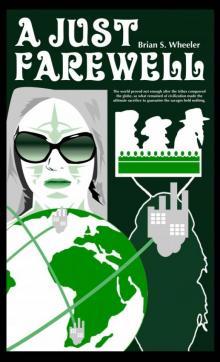

Zombies Earning Their Hunger A Just Farewell

A Just Farewell